As of January 1, 2024, most U.S. businesses with fewer than 20 employees will have to register with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) of the U.S. Treasury Department.[1] Read on for what your business needs to know about this new obligation.

The Corporate Transparency Act

In 2021, the Corporate Transparency Act[2] was enacted as part of the National Defense Authorization Act in an effort to better enforce anti-money laundering laws. The law seeks to make it more difficult for business owners to hide unlawfully obtained assets, hide identities, and launder money through the financial system of the United States. The law is also intended to make corporate ownership more transparent. The law became fully effective on September 29, 2022, when the final regulations were issued.[3]

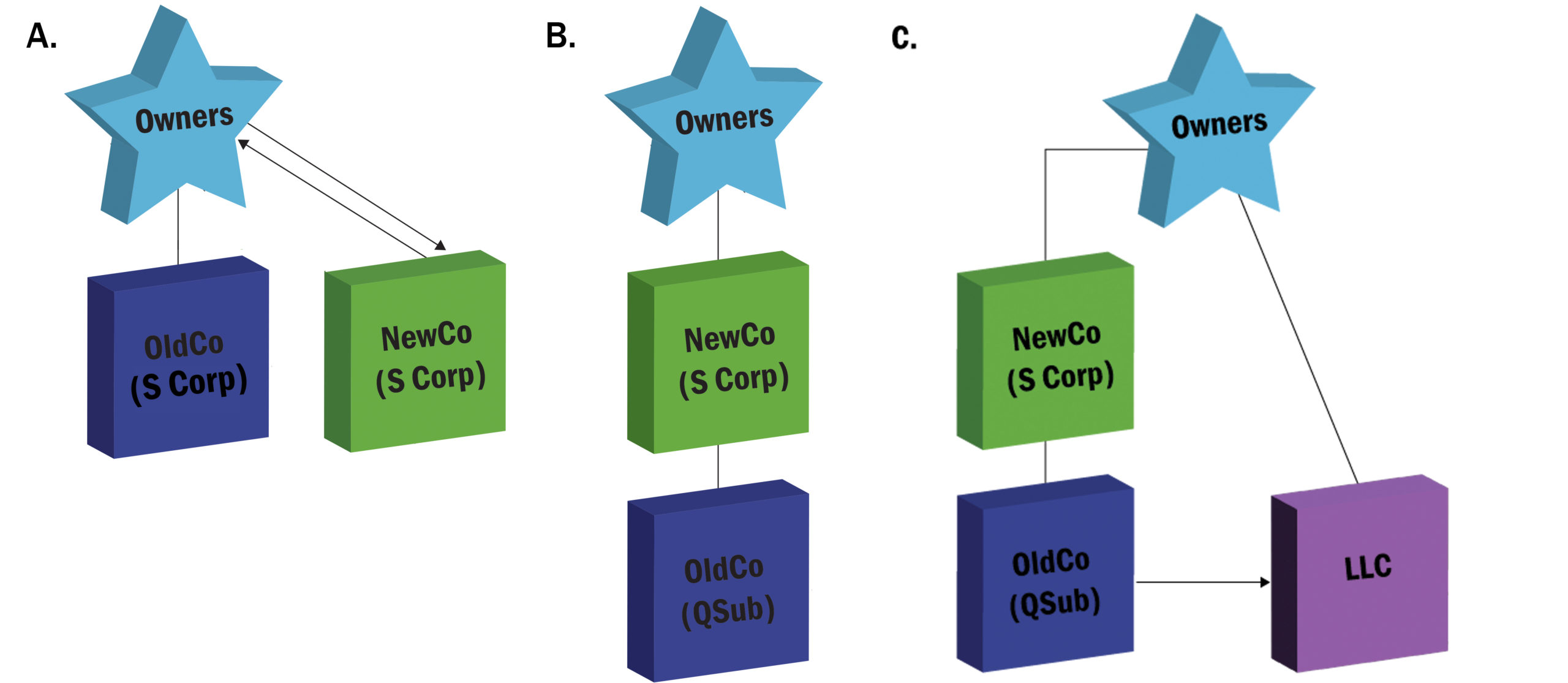

This federal law requires certain business owners to provide the federal government with specific details on the owners of the business, as well as on other persons who benefit from the business operations. A business that must report is called a “Reporting Company,” which the Act defines as a “corporation, limited liability company, or other similar entity that is created by the filing of a document with a Secretary of State or a similar office under the law of a State or Indian Tribe” (so sole proprietorships or partnerships that are not separate entities do not need to report). However, an entity formed outside the United States which registers to do business in a State is subject to the law.

Who Reports What?

Reporting (at approximately $85 per business) is required of those U.S. corporations, LLCs, or similar entities with 20 or fewer employees. Why is 20 employees the threshold? It is believed that most shell companies being used to hide unlawful assets have few, if any, employees.

The largest exemption from filing is believed to be “large operating companies,” those with more than 20 employees, operating in the U.S. (from a physical business address, not a home office) with over $5 million in sales or gross receipts. Additionally, banks, credit unions, insurance companies, accounting firms, public utilities, governmental authorities, security brokers, and others who report ownership to the government under other laws are exempt from registration under the Act.

Existing, active businesses covered by the Act will have one year to report:

- the company name, trade name(s), business address, state of formation, Employer Identification Number (EIN), and

- the name, date of birth, residential or business street address, and one unique identification number (i.e., driver’s license, passport, government issued identification) with a copy of the document from which it came, of all “Beneficial Owners,” people who own, substantially control, or create the company (the “company applicant”).

Businesses must make the initial filing, then again every time there is a change in Beneficial Owner status.

Beneficial Owners

A Beneficial Owner is any person who, directly or indirectly, owns or controls 25% or more of the entity, or who exercises substantial control over the entity. Substantial control is defined to include any person who serves as a senior officer, has authority to appoint or remove senior officers or members of the board of directors, or who provides direction or makes decisions about a company’s “important matters.” The ownership or control that triggers reporting obligations may exist in not only corporate or business governance documents, but also through separate contracts, arrangements, relationships, or understandings.

However, Beneficial Owners are not minor children (assuming the child’s parents/guardians are reported), an individual acting solely on behalf of another person (an agent, nominee, custodian, etc.), a non-owner employee of the entity, creditors, or individuals with inheritance interests only.

Penalties

Any changes in Beneficial Owner statuses must be reported within 30 days of the change.

Penalties for willful non-reporting are both civil ($500 per day) and criminal (up to two years in prison and/or a $10,000 fine). The Reporting Companies are required to comply with this reporting law, not the Beneficial Owners themselves. These are most definitely safe harbors, which permit the sidestepping of liability for failure to report.

Safeguarding of Information

The U.S. Treasury Department is tasked to create a database to house the personal information of what is believed to be over thirty million businesses throughout the country.

The database will be accessed only by law enforcement, banks, and the government. FinCEN is responsible for safeguarding the financial system of the United States from illegal activity, including not only money laundering, but also fraud, corruption, and financing of terrorist activities. Ironically, a law intended to combat fraud may lead to potential concerns about safeguarding the sensitive information collected.

For further guidance, compliance information, and updates, please contact us.

[1] According to the New York State Department of Labor figures, in 2021 90% of all businesses on Long Island had between one and 19 employees.

[2] For full text of Act, see https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr2513/BILLS-116hr2513rfs.pdf.

[3] See https://bostontaxinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/boston-tax-institute-public-inspector-regs.pdf and generally https://www.fincen.gov/beneficial-ownership-information-reporting-rule-fact-sheet.